A major digitisation project is under way in the Department of History and Philosophy of Science to develop a detailed online record of the thousands of casebooks of Simon Forman. A doctor and self-proclaimed master of the ‘hidden’ arts of the occult,...

“Taking this seriously as a framework for how some people lived their lives enables us to see how this made sense to Forman, and to the people he treated”

Dr Lauren Kassell

On a Thursday evening in September 400 years ago, Simon Forman’s wife asked which of them would die first. Forman – at the time one of London’s best-known astrologers, occultists and physicians – replied that he would be dead within a week. By the following Wednesday, the doctor was alive and well, his morbid prophecy happily in question. But the next day he collapsed and died on a boat from Lambeth, crying ‘an impost!’ as he fell, just hours before his prediction elapsed.

Mere coincidence, or was Forman a victim of his own occult powers? It’s hard to look on such stories without scepticism from our vantage point in the 21st century, but Forman lived at a time when magic and medicine were often two sides of the same coin, and astrology was a serious business.

For Dr Lauren Kassell, Director of the Casebooks Project – an online database making available the astrological records of Forman and his pupil Richard Napier – the context in which Forman was working is vital to cataloguing the casebooks.

“Astrology is one of the longest-standing intellectual traditions in the world, dating back to ancient Mesopotamia,” she says. “Taking this seriously as a framework for how some people lived their lives enables us to see how this made sense to Forman, and to the people he treated.

“Forman’s clients did not believe in astrology in a simplistic way. Someone today with back pain may take a vitamin supplement. That doesn’t mean they believe it is going to completely solve the problem, but they try different approaches. This kind of medical pluralism has been around for hundreds of years, and astrology was a part of that.”

Prison, pirates and medical practice

Simon Forman’s life was as extraordinary as his demise. A self-made man, he reinvented himself as a teacher of medicine and magic after dropping out of Oxford University. Following a troubled 20-year period that saw him serve a string of prison sentences and get taken captive by pirates, he settled in London in 1592 and established his practice.

For the next 19 years, his growing success as a doctor and astrologer led to a prolific output of case notes – some 50,000 when combined with those of Napier – which provide a unique insight into the lives and beliefs of people at the turn of 17th century England.

This wealth of material is a phenomenal resource. When matched with the benefits of the latest digitisation techniques, the potential is vast, as Dr Kassell explains.

“This project is the perfect marriage between ambitious editing and high-end digital humanities. Every single case is coded with layers of meaning, so that when the project is complete, you will be able to interrogate the data from any direction: age; date; name; condition; diagnosis and so on. It will be a bit like Google Earth for the casebooks, enabling us to zoom in and out, seeing what we need in the records, then stepping back to analyse.”

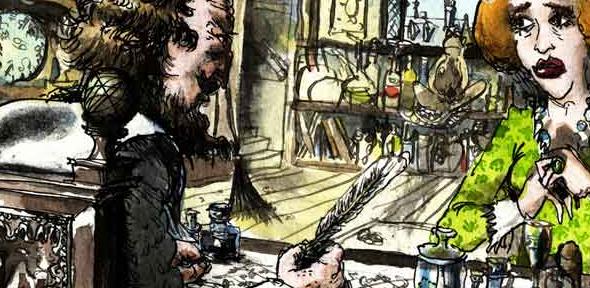

We have Forman’s diligence as an astrologer to thank for the quality and quantity of his casebooks. The state of the cosmos at the moment a person asked a question was considered crucial to the ensuing prediction, so a good astrologer was constantly taking notes. Forman would have had a quill in his hand at most times during a consultation.

The majority of the cases related to health – questions such as: ‘what is my disease?’ or ‘am I pregnant?’ – but other concerns such as fortune and fidelity crop up. Once the question had been asked, the reading could begin, and Forman would ‘cast a figure’, an astrological computation of the stars.

Celestial configurations

Thousands of celestial configurations were possible, and the chart would result in a verdict on the cause of the disease, the luck of the merchant or the dalliances of the lover. A figure could be cast for any question. On one occasion Forman cast a chart in an effort to find his missing socks.

In some ways, Forman was a precursor to the modern GP, adopting the model of a single practitioner managing his patient’s health from diagnosis to treatment. “In fact, Forman’s service was more complete than a modern GP’s, as he provided the diagnosis, prescription, and even minor surgery as necessary,” says Dr Kassell.

At a time when the physical and mental were still quite indistinct, there is an awareness of psychology in the casebooks that stands out. Forman deliberately fostered a sense of doctor-patient trust, which he saw as elemental to his work. He relates to his patients, particularly women, appearing at times to be a sort of Elizabethan therapist.

“A lot of women would talk to him about their sex lives,” says Dr Kassell. “It is clear that he thinks a woman’s sexual activity is fundamental to her health. One of my hypotheses is that part of Forman’s success was down to the fact that women felt they could approach him to discuss sexual issues.”

Sex was at the heart of the events that would tarnish Forman’s reputation for centuries. One of his eminent clients was the Countess of Essex, who lusted after Robert Carr, a rising star in the court of James I. The countess consulted Forman, and he allegedly provided her with magic that not only swayed Carr to return her desires but also rendered her then husband impotent, one of the few grounds for divorce at the time.

Carr’s friend, the poet Thomas Overbury, spoke out vehemently against the union, and was incarcerated in the Tower of London in deference to Carr, a favourite of the King. Overbury died five months later. In 1615, four years after Forman’s death, a scandal erupted when an investigation revealed that the countess had poisoned Overbury to silence him, and the crime had been covered up.

At the ensuing trial, evidence of Forman’s involvement was presented, including magical symbols and obscene wax figures. “He was demonised during his lifetime by the Royal College of Physicians, but particularly around the Overbury scandal the language is very strong,” says Dr Kassell.

“At one point during the trial, one of the benches snapped in two. It was thought that this was the devil expressing anger that his handiwork, as crafted by Forman, was on display. The presence of the devil was a terrifying notion at that time.”

Summoning spirits

The legacy of the trial was that Forman became a stock character, wheeled out in popular culture – from Jacobean plays to 19th century novels – as the evil magician in cahoots with the devil, eclipsing the populist renown of his heyday.

Not that he was entirely innocent of attempting such connections. There are accounts of him trying to summon spirits, an act that always carried a risk of the devil showing up, although he doesn’t appear to have got very far.

“Forman gets frustrated because all he can muster is the smell of sulphur and a few puffs of smoke. I found an account in which he suggests that he lacks the purity to traffic with the spirit realm as a result of his other appetites.”

Astrologer du jour or devil doctor? Master of the occult or spinner of tall tales? Despite the casebooks Forman remains an enigma. However he is thought of in years to come, it is clear he will continue to be thought about.

Dr Kassell is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of History and Philosophy of Science. The newly launched website for the Casebooks Project can be found at www.magicandmedicine.hps.cam.ac.uk