From 1603 to 1950 the University sent two MPs to the House of Commons, among them two Cromwells, two future Prime Ministers and an FA cup winner. But do academics make good politicians and do we need more of them in Parliament today?

Sir Isaac Newton's only recorded contribution to Commons debate was his request to shut a window.

From St Ives in west Cornwall to Orkney and Shetland, there is scarcely a parliamentary seat in Britain that has not been occupied by a Cambridge graduate. But within living memory, the University has also been a constituency in its own right, and had the power to send its own MPs to the House of Commons.

Dr Elisabeth Leedham-Green, archivist at Darwin College and author of A Concise History of the University of Cambridge, says: “Those qualified to vote for the University MP also had another vote, so chaps in Cambridge might be able to vote in, say, Huddersfield, and graduates domiciled in Huddersfield could also vote for the University MP, provided they had kept their names on the college books by paying an annual fee.”

The Parliamentary constituency of Cambridge University was established in 1603. On acceding to the English throne, James VI of Scotland decided that the practice of the Scottish Parliament – which granted seats to the country’s five ancient universities – should be followed south of the border. The universities of Oxford and Cambridge were duly enfranchised by Royal Charter, each sending two members to the Commons.

The constituencies would persist in this form, more or less, until their extinction at the 1950 General Election; and at various times throughout the next 350 years, the Oxbridge MPs were joined at Westminster by representatives of other seats of learning in the British Isles.

The Cambridge University constituency observed several peculiar practices. Elections seemed subdued, compared with the usual tumult of a Parliamentary campaign. The poll was generally open for several days, and took place a leisurely couple of weeks after the main election. Candidates were not expected to canvass in person, and were banned from coming within ten miles of Cambridge at this time. Many candidates stood as independents, and several elections were uncontested 'coronations’.

FA Cup finalist

Members chosen by Cambridge graduates included prominent figures from many walks of life. Though Oliver Cromwell represented the town constituency, two of his sons became MPs for the University: Henry in 1654 and Richard two years later. Two prime ministers were University of Cambridge MPs, Pitt the Younger and Lord Palmerston. And one MP, John Rawlinson, had the unique distinction of playing in an FA Cup final. The lawyer and jurist kept goal for Old Etonians in their 1882 victory over Blackburn Rovers.

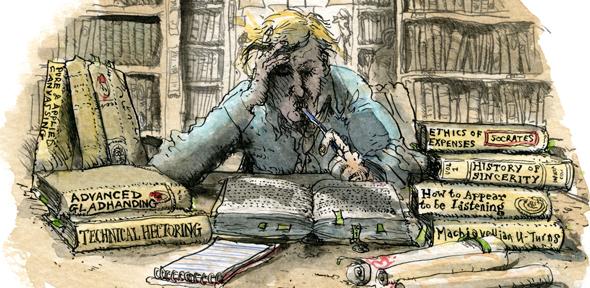

From Francis Bacon in 1614, many Cambridge-educated scientists and academics represented the constituency. Most eminent was Isaac Newton, although his only recorded contribution to Commons debate is a request to shut a window. “The most celebrated Cambridge politicians were, speaking very roughly, not distinguished academics,” says Dr Leedham-Green. “Newton was certainly a distinguished academic, but notably not a great parliamentarian.”

Later academics managed to straddle both worlds more successfully. The mathematician and physicist Sir Joseph Larmor (University MP from 1911 to 1922) was known in the House for his zeal against Irish Home Rule and spoke on such matters as vivisection, electoral reform and the upkeep of London’s Science Museum. None of his citations in Hansard, though, are as quotable as his 1920 plea to the governing body of St John’s, when the College proposed to install baths: “We have done without them for 400 years. Why begin now?”

Among the most successful parliamentary dons was physiologist Archibald Vivian Hill, one of the few Nobel Laureates to sit on the green benches. During World War II, Hill was an important member of the War Cabinet Scientific Advisory Committee but became best known as a fervent promoter of scientific inquiry for its own sake. Most famously, he asked: “Would you ask a mother what practical use her baby is?” when pressed on the practical use of complex research in the pure sciences.

Though Cambridge’s history includes no shortage of friction between town and gown, little of it seems to have been played out in the Commons chamber. A large quotient of town MPs were University alumni, prone to identify the interests of the one with the other.

Town-gown tensions were not the only ones to concern University MPs. Dr Leedham-Green says: “Elections to University offices were very often along party lines, with which inter-collegiate rivalries roughly, but never precisely, coincided. The challenges would have included trying to keep both Trinity and St John’s on side – something that was very difficult. But Pitt and Palmerston, for example, seem to have managed.”

By the mid-20th century, Oxford and Cambridge University constituencies represented quite an anomaly. They were among a small number of surviving multi-member constituencies and unlike the geographical constituencies they used the Single Transferable Vote – the only example of proportional representation ever having been used in Westminster elections.

Abolition of university seats

The rise of the Labour Party coincided with growing calls for abolition of the university seats. One criticism was that they offered a back door into Parliament for those defeated elsewhere. The most notorious case was that of the first Labour prime minister, Ramsay MacDonald – who, in the words of one university MP, “having brought in a [failed] Bill to abolish the university franchise, was himself defeated in the General Election of 1935 and was glad to take refuge in a Scottish university seat.”

Clement Attlee’s government finally called time on the university seats with the Representation of the People Act 1948 – legislation that also swept away other forms of plural polling, such as the extra vote held by owners of a business located outside their home constituency. But university seats had their champions until the end.

Some suggested that the seats could be retained, but graduates confined to voting in either a geographical or an academic constituency. Prominent in this camp was the Master of Trinity, George Macaulay Trevelyan. He wrote in a letter to The Times: “It seems a pity that for the purpose of abolishing the plural or alternative vote, a valuable institution like university representation should disappear ... It still supplies the House with a number of men, most of whom are not attached to either party and who bring an element of which both parties stand in need.”

Trevelyan lauded the contribution of scientists to the Commons – mentioning both Newton and AV Hill, who “represented not a party but science”. But there were equally fierce opponents of the notion that academics were an injection of independent, disinterested wisdom into the body politic.

One outspoken critic was diarist and future cabinet minister Richard Crossman. Debating the abolition bill, he told the House: “We have been told that we want plenty of dons in the House... so that we can have that peculiarly independent judgment which professors maintain. I have never found any peculiar independence about them. Professors are as prejudiced and as partisan as any other members of the population.”

Crossman went on to state his preference for dons who “go through the usual rough and tumble of an election and get elected to Parliament in the ordinary way”. And in the case of Cambridge – the single seat that now encompasses town and gown – the late politician’s wish has been granted, as the past two general elections have delivered University academics to the Commons.

PhDs in the Commons

David Howarth, a Reader in Law and Fellow of Clare College, was succeeded in 2005 by Dr Julian Huppert – an RCUK Academic Fellow in Computational Biology at the same college. “I went to school here so I feel part of both town and gown, to the extent that they’re still separate,” Huppert says. “It’s important to represent all of Cambridge, from leafy University areas to council estates.”

Does he think that his scientific background informs his approach to politics? “Having a different background from other people is very valuable; it means you can come in with an insight others might not have,” he says. “Amazingly, there are only two of us with science PhDs in the Commons, and I’m the only one who went on to do research.”

Huppert thinks Trevelyan's view that academics bring valuable skills to Parliament has merit. “For instance, there’s a real issue when the Government does a U-turn,” he says. “But I’m actually quite in favour of politicians changing their mind after a consultation. Otherwise, what’s the point of the consultation?

“I think that’s something academics are good at: coming up with an idea, but when the evidence comes in, being prepared to accept that there’s a better idea. I’d like governments to do that a lot more.”