A study by Cambridge criminologist Professor Manuel Eisner has revealed statistically just how dangerous it was to be a king or queen between 600 and 1800 AD.

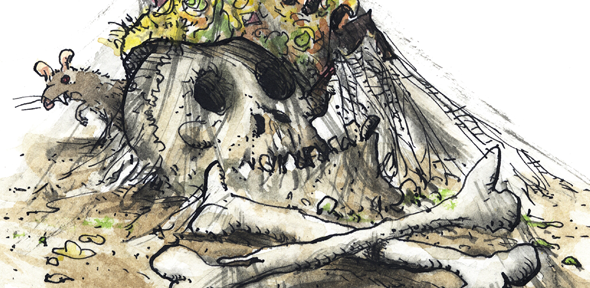

Few roles are as high profile as being a royal, something that Prince William and Kate Middleton know all too well. In the past, however, ruling members of royal families found themselves not only attracting a huge amount of attention but also quite literally in the firing line, with their lives in danger from rivals and revenge-seekers, rebels and revolutionaries.

The astonishing number of European kings who met a violent end has been documented by University criminologist Professor Manuel Eisner. His study Killing Kings reveals just how risky it was to be a monarch in an era when murdering those who stood in your way was a fast lane to power.

Killing Kings is the first statistical study of the demise of 1,513 monarchs in 45 European monarchies, covering the period 600 to 1800 AD. It reveals that almost a quarter (22 per cent) of all royal deaths were bloody – accidents, battle deaths and killings – and that 15 per cent of all deaths were outright murder.

“The toll of 15 per cent corresponds to an average rate of ten murders for every 1,000 years of life as a monarch – far higher than the homicide rate for even the most troubled areas of the world today,” says Professor Eisner.

“This rate is higher than the threshold for ‘major combat’ among soldiers engaged in a contemporary war. It demonstrates the intense violent rivalry for domination among historical European political elites.”

Manuel Eisner is Professor of Comparative and Developmental Criminology and Deputy Director of the Institute of Criminology. His research interests revolve around two main areas: macro-level historical patterns of violence; and individual development and the causes and prevention of aggressive behaviour.

As a criminologist, he divides his statistics for kingly killings into four broad scenarios. Top of the list is murder as a means of succession: at a stroke the reigning monarch is removed from power and a rival enthroned. An example of this came in 969, when the Byzantine Emperor Nikephoros II was slain in his bedroom by his wife Theophano and his chief general, John Tzimiskes. John was crowned emperor after agreeing to do penance for murder and to separate from his lover.

Next up is murder by a neighbouring ruler and competitor, attempting to gain territory or seal a military victory. In 1362, the Sultan of Granada, Muhammed VI, was invited to attend peace talks with the King of Castile and murdered treacherously near Seville on the orders of Peter I of Castile.

Personal grievance and revenge, fuelled by rape, murder or insult committed by the ruler, rank third as scenarios. Such a fate befell Albert I of Germany, who was assassinated in 1308 by his nephew Johann of Swabia and others while riding home from a banquet at which he had publicly insulted Johann.

Bringing up the rear is the outsider killing. In 1172 the Venetian Doge Vitale Michiel II was stabbed to death by a member of an angry mob. In 1354 Yusuf I, Sultan of Granada, was killed by a maniac while praying in the mosque.

Young monarchs – whose grip on the reins of power was tenuous – were especially liable to having their lives cut brutally short. Most poignant are the presumed murders of young Prince Edward V and his younger brother Richard in the Tower of London. In some cases, murder begat murder in relentless waves of killings. Murder hot spots cropped up in some unlikely cold climates – among them Norway and Northumbria.

Professor Eisner suggests that the murder of monarchs provides a window into the dynamics of elite violence across more than a thousand years of European history. If removing a monarch promised important benefits, and opportunities arose, assassination was seen by political elites as a swift route to regime change.

European regicides were most frequent in the early Middle Ages and became gradually less common over the centuries. Professor Eisner suggests that, as legislative systems strengthened their hold on the division and transfer of power, murder lost its appeal as a strategic tool. On top of this, the doctrine of the divine right of kings, which gathered credence from James I onwards, meant that kings enjoyed almost godly status and an act of deposition was deemed sacrilegious.

“After the 16th century it became very uncommon to organise power transfer through the murder of a monarch. If it did occur, it required extensive legal justification, such as in the criminal trial of Charles I in 1649, which eventually led to his execution,” he says.

“As for regicides motivated by ideology and radicalism, they have continued right into the early 20th century.”